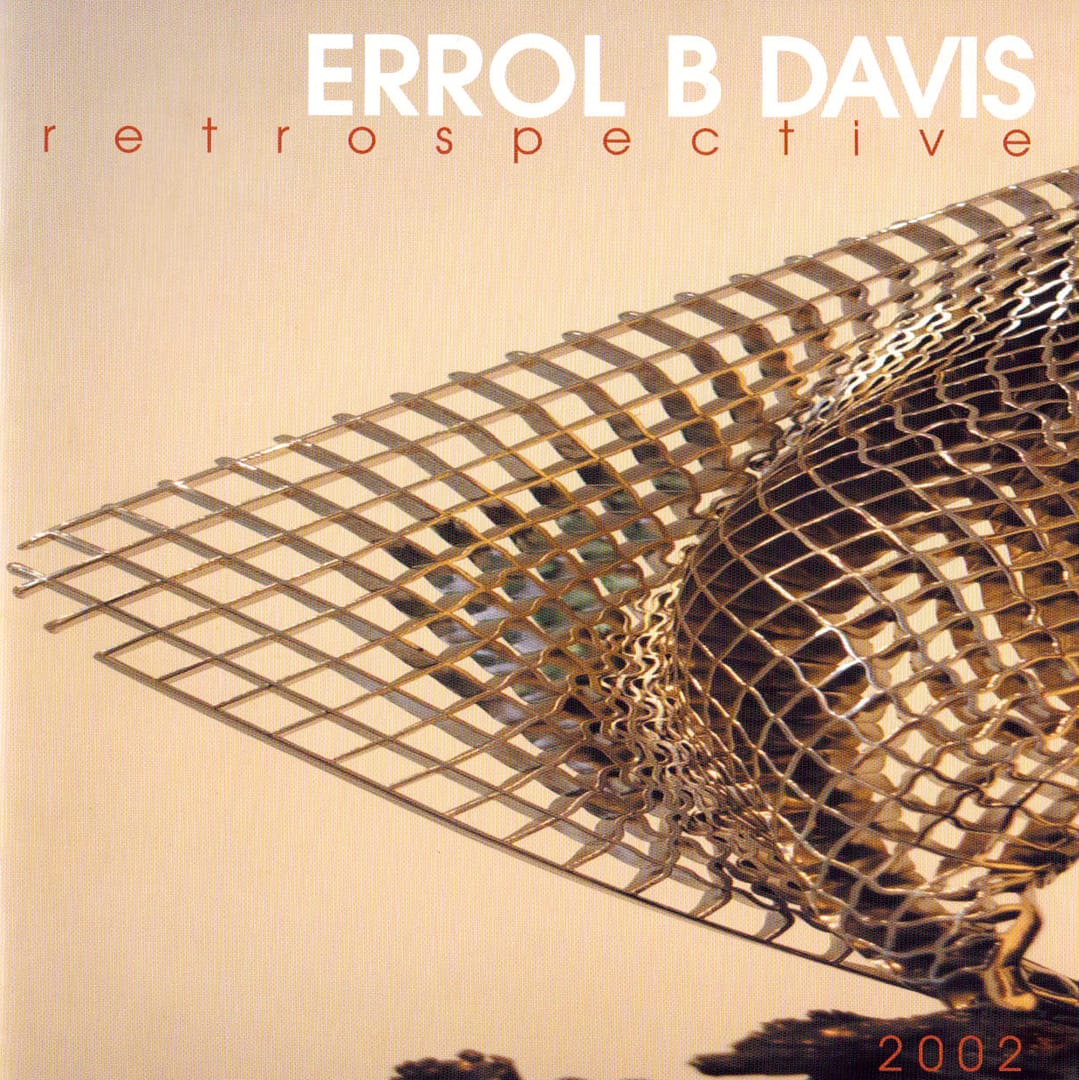

2002 Solo Exhibition:

Errol B Davis Retrospective

Macquarie University Art Gallery

Errol Davis held more than a dozen solo exhibitions of sculpture and tapestry between 1973 and 2002.

This page contains the catalogue of Errol’s final exhibition of sculpture, his 2002 Retrospective, as well as additional photos taken while setting up the exhibition.

“Davis’ sculptures breathe the environment. His observations of the contour of the land, of the patterning of a leaf or the way a plant grows adds the essential ingredient to his work – poetry.

He believes that sculpture is a link to poetry, with poetry and rhythm being common to both art forms. Davis’ interest in nature, coupled with the multitude of ways he could manipulate his contours, meant he is working in a way and with a material like no other artist in Australia.”

– Stella Downer, from the foreword of Errol’s 2002 Retrospective catalogue.

Read the full foreword, as well as Errol’s interview with Vice-Chancellor Di Yerbury, further down this page.

“I never copy Nature. Although my work does refer to Nature.” – Errol Davis

To see the rest of the catalogue, scroll down past the photo gallery or tap here.

- All

- Acrylic

- Bronze

- Electroplate

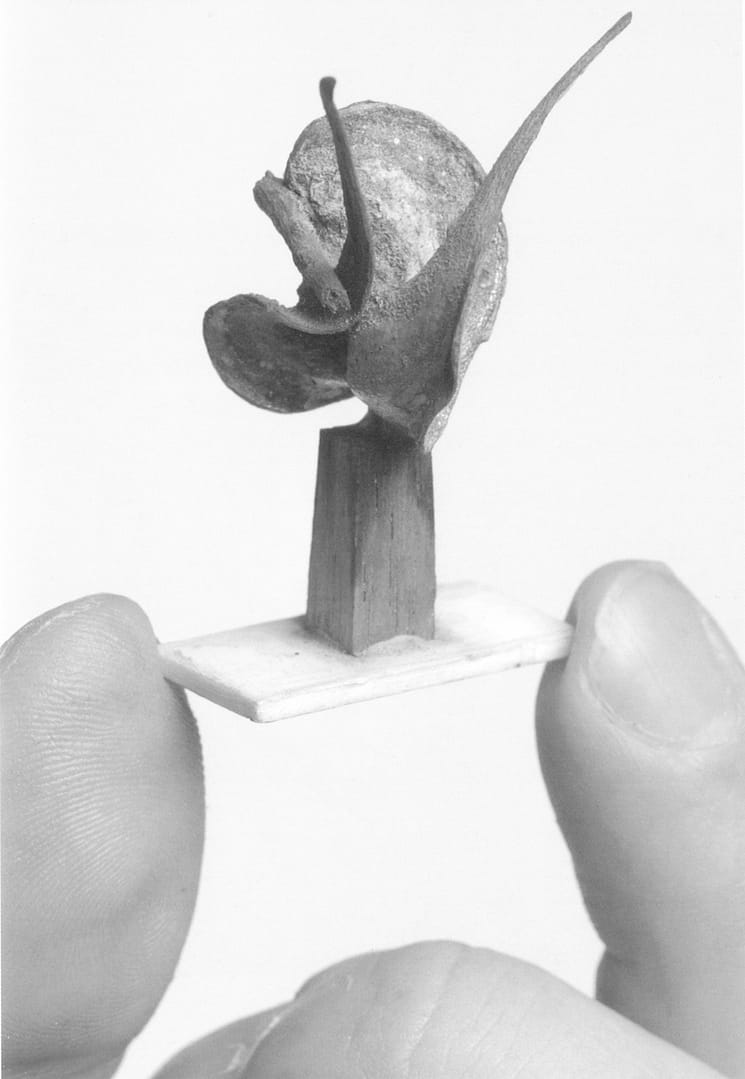

- Maquette

- Resin

- Steel

- Wood

Foreword to the 2002 Retrospective catalogue, by Stella Downer

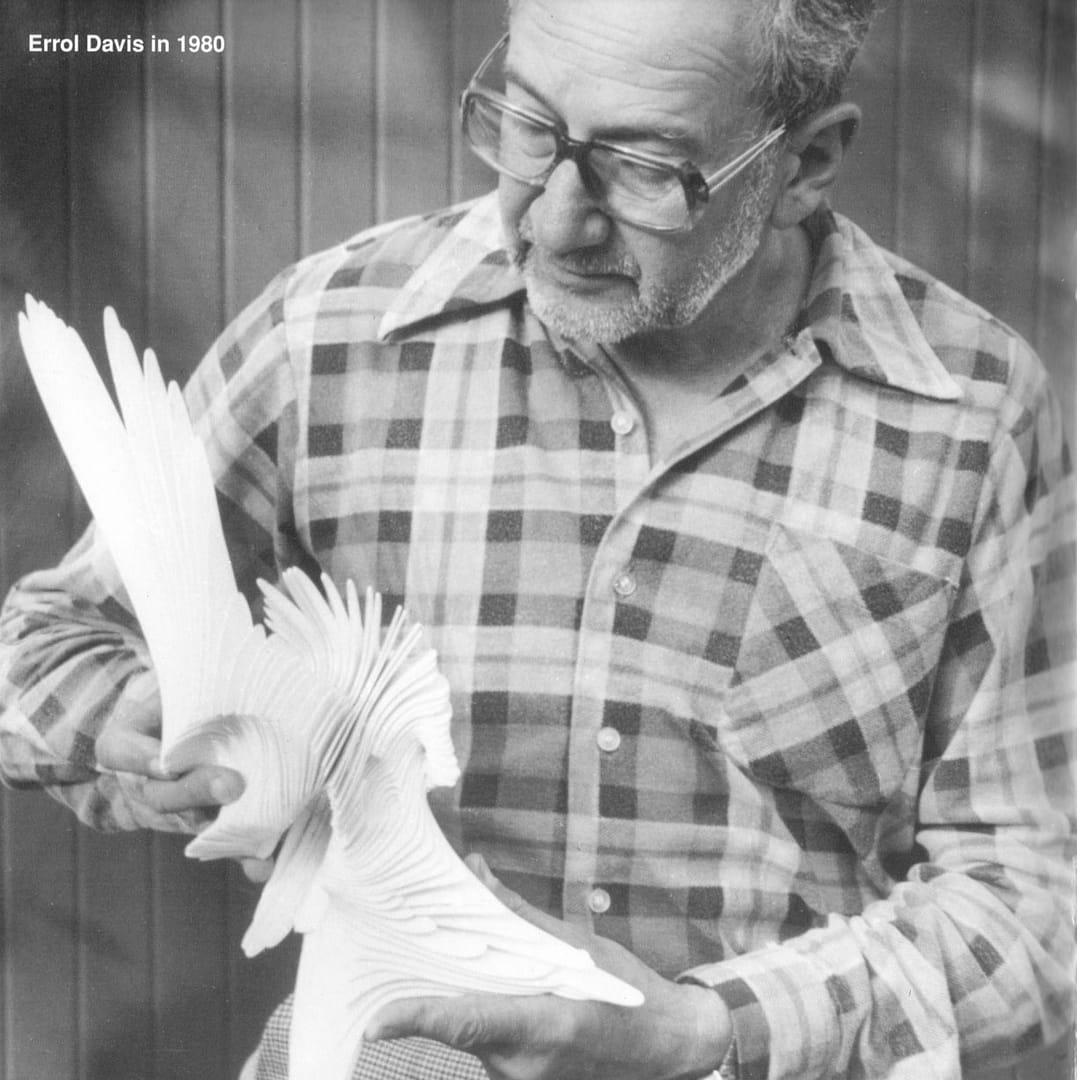

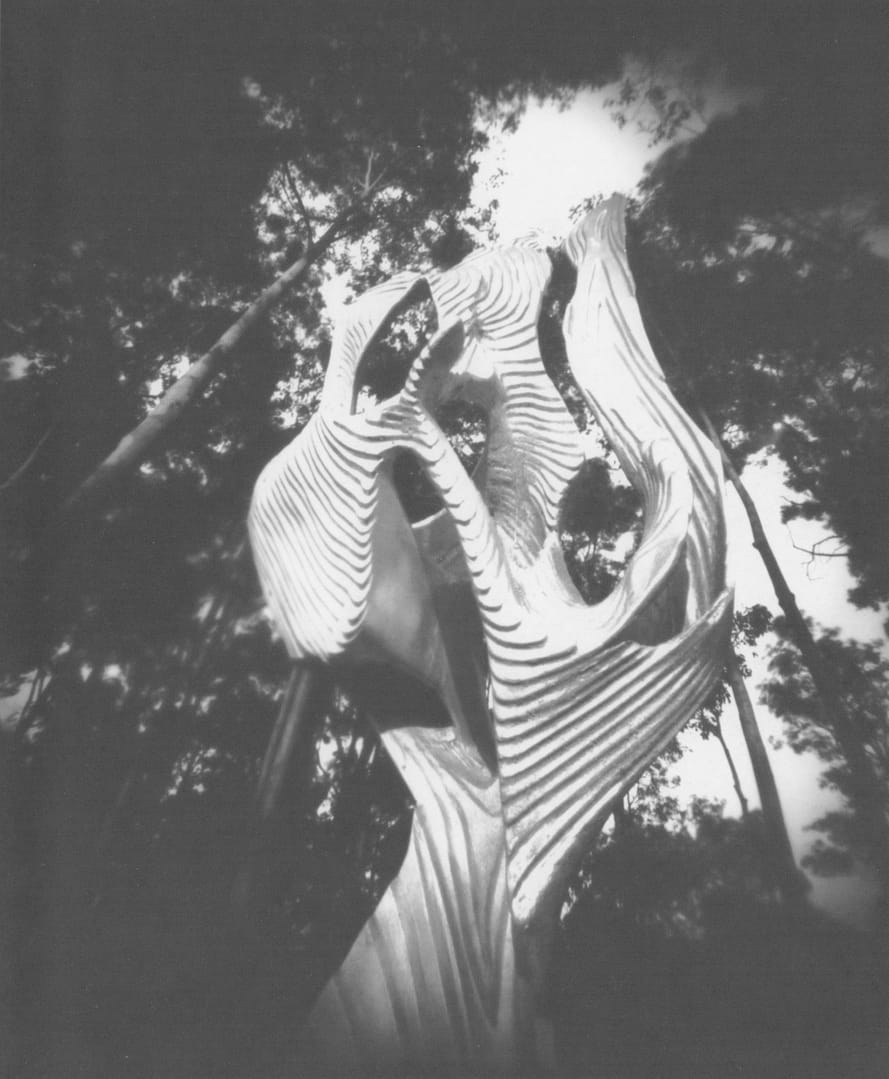

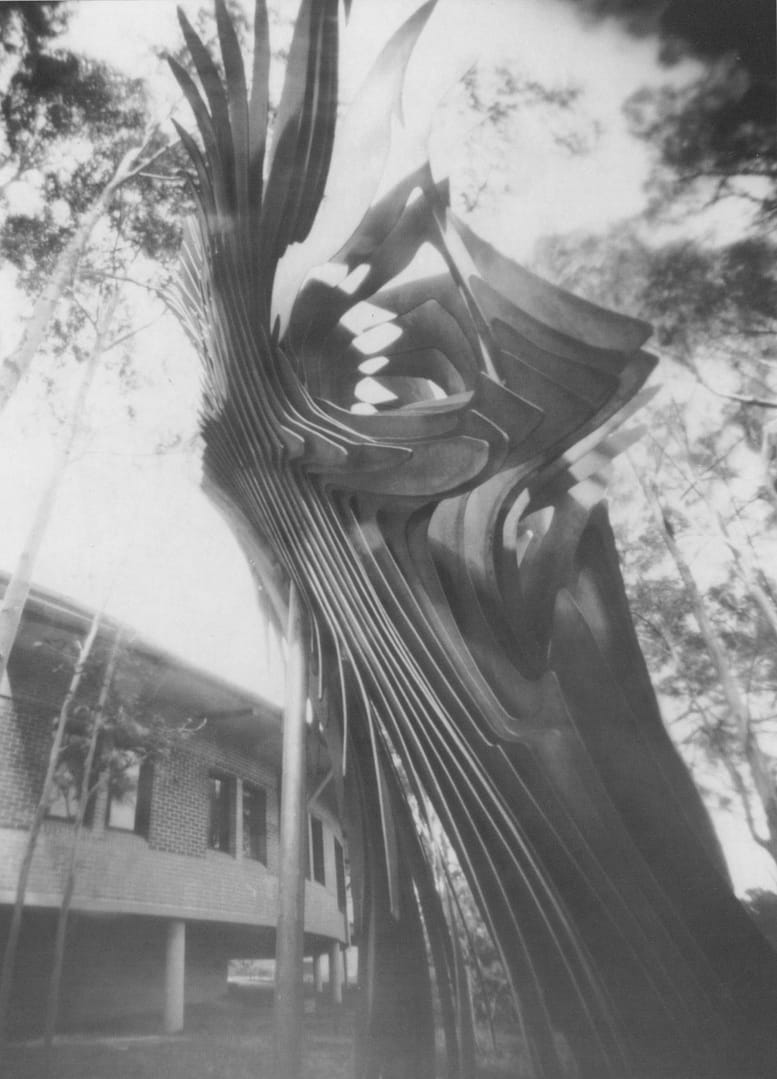

More than in any other area of the arts, sculptors in the last 20 years have rethought their work in relation to discussions about the rise and fall of Modernism and Postmodernism. Here the boundaries between 2-D and 3-D, or the concept and the object, are constantly blurred. To Errol Davis, sculpture is a happy blurring of object and poetry. In an often confusing visual world of conceptual puns and gimmicky one-liners, it is refreshing to find a sculptor such as Davis, who is so obviously rooted in an age-long practice of art as an object. Davis’ sculptures in stainless steel, metal and bronze are also about new technical innovations and here lies a tension, an essential ingredient in any lasting quality.From an early age, Davis had an interest in building models. In fact he established a business specialising in scale models. One of his clients was Macquarie University. His strong need to make objects soon found a voice in his much more substantial sculptures. Here his training as an engineer came to the fore. From working with models to the cutting out of relief maps in plywood grew the finely worked out contours in stainless steel. With Davis’ discovery of the laser cutting machine, he gave new life to his sculptures through the flexibility and strength of the stainless steel. He devised a way of fanning out each form with such delicacy to appear like the pages of a book, creating light and air between each page.

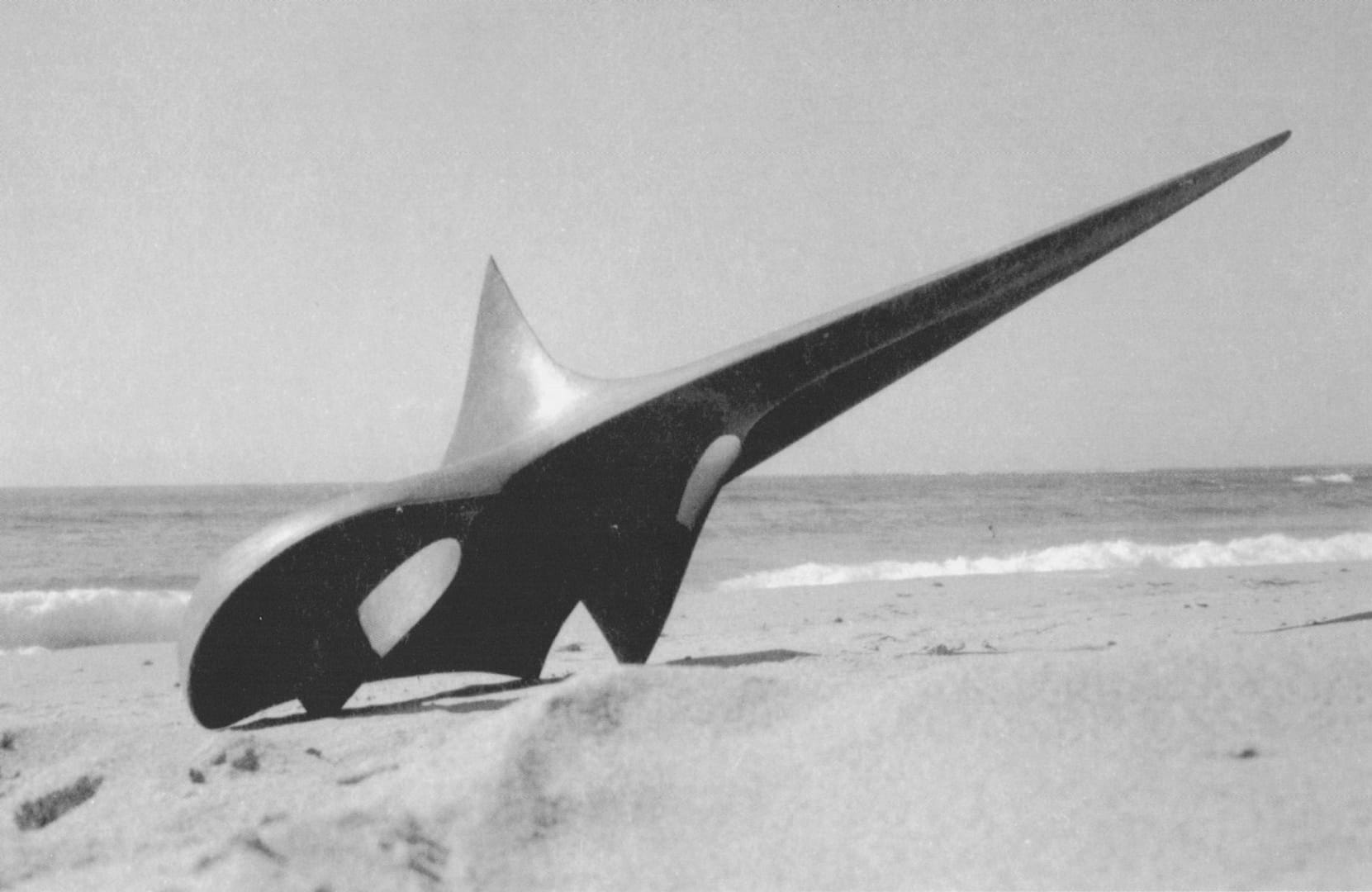

Davis’ sculptures breathe the environment. His observations of the contour of the land, of the patterning of a leaf or the way a plant grows adds the essential ingredient to his work – poetry. He believes that sculpture is a link to poetry, with poetry and rhythm being common to both art forms. Davis’ interest in nature, coupled with the multitude of ways he could manipulate his contours, meant he is working in a way and with a material like no other artist in Australia.

We are all recipients of Davis’ foresight and altruism. His vision of the Macquarie University Sculpture Park has opened out to the community a thousand ways of appreciating sculpture; it has created a University gallery and a curator and a new department. Thank you Errol Davis.

Errol interviewed by Di Yerbury, Vice-Chancellor

My father was a keen handyman and when I was a toddler, say 3 or 4, I’d pick up the pieces of wood left over when he was working, and try to make things. I still have a scar on my hand where a knife slipped. I was always a bit impatient.

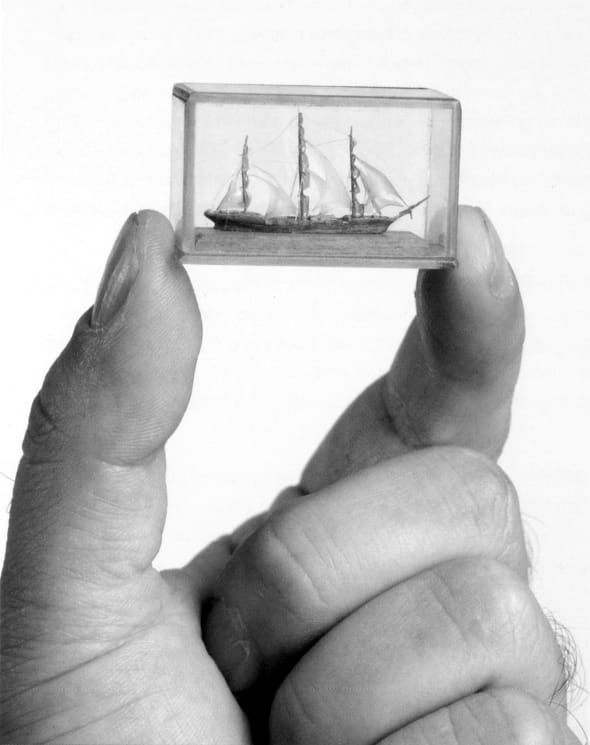

I used to take pieces of wood and hammer on wheels or whatever. Really they were sculptures. It seems like only yesterday … As I grew towards my teens at Sydney Boys’ High School, I made boats and ships and aeroplanes, and gave them to friends. Mainly they were in wood: there were no plastics in those days.

During the war, there were no metals either; they were all used for the war effort. I made painted wooden ships which were a substitute for Dinky toys. I sold them at the newsagent’s shop, where they didn’t last very long: there was a demand for them. I wish I’d kept them. I feel proud of them now, more than I did then, when I was just earning pocket money.

About 1942 I was contacted by Sir Frank Packer as someone who made model aeroplanes, and asked to join an outfit called the Volunteer Air Observer Corp. There was no radar in those days, and we made model aeroplanes on a volunteer basis and used them to educate people about the appearance of enemy aircraft.

It was me and Lloyd Rees; we formed a team. And there was a girl, Marnie Monk – most unusual to find a girl making model aircraft. There was another volunteer organisation for the Navy, to educate people about ships. Robert Klippel was doing that.

All these model aeroplanes were hanging from the ceiling of the penthouse in the Astor in Macquarie Street. They were on a scale of 6 feet to the inch. I still have some of them – and a little model aircraft I made for myself on a different scale, a very tiny thing.

I studied Engineering Technology – that’s what we used to call it then; nowadays we call it Chemical Engineering – at Sydney University. After graduation I worked as an Assistant Engineer at Colgate Palmolive. My parents decided on engineering because that was the closest to what I was doing at home. Perhaps that wasn’t the right decision … but one doesn’t talk about ‘what ifs’. And being an engineer has been a great help in what I did later: I wasn’t just an artist.

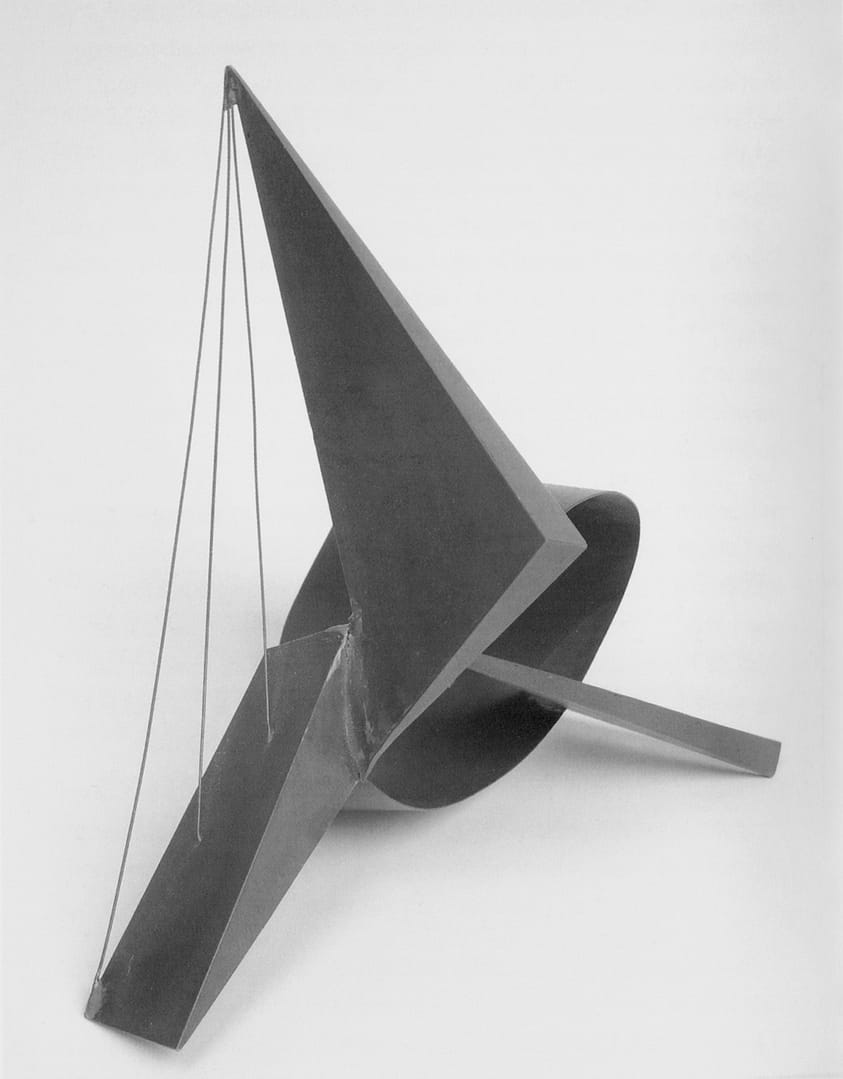

During that time I started to do what is now called ‘sculpture’. In those days I don’t know what I called it: I just liked making these things. The scene for sculpture was very grim. People thought I was crazy. My mother would say, ‘What’s it supposed to be?’ and people would scratch their heads. But I think now they were quite good sculptures for someone who was barely twenty.

In London, where I arrived by ship in 1950, I had to earn a living so I didn’t have time to do anything big. But some of those miniatures I did then could be turned into something quite large even now. London was fantastic. I met Trudy there at the same time as the Festival of Britain and got engaged. Oh, London was wonderful! I think it must have been at its peak. The Festival Hall was going up, and there were Henry Moores and Barbara Hepworths all over the place. I was immensely inspired by them.

There was a sculpture park in Shepherd’s Bush, and a major sculpture exhibition called The Unknown Political Prisoner, which was won by Reg Butler – I thought his works were about as crazy as mine.

I was making small sculptures in our flat. Then I changed my job to a firm which manufactured things out of copper. Great pieces of copper were being thrown away as scrap. I was allowed to go down every lunch hour to the workshop and play around with it. One sculpture I entered in an exhibition called Artists from the Commonwealth received quite a lot of acclaim. Barry Humphries – he was a painter in those days – had some work in that show, too.

We got back to Australia in 1955, and again I worked as an engineer, for about three years. I bought a block of land in Turramurra where we live now, and I designed a house for it, and made a model of it, and an architect asked whether I’d make models for him. I wasn’t sure, but then as fortune would have it I was retrenched. I’ve never worked for anyone since.

I was deluged with orders for models, and before long I had a couple of people working for me whom I trained. Then there was the building boom in Sydney, and for every building a model was needed.

One of my clients was Wally Abraham [Macquarie’s founding Architect-Planner]. Before the first sod was turned they had me doing models of buildings for this campus.

But I never stopped making sculptures. And I was getting frightfully bored making models of other people’s designs. I wanted to do something myself. I realise now that, theoretically, I should have practised sculpture from the very beginning, but I needed to support a family. I have no regrets about that.

I started to work in wood, and a lot of my inspiration came from the models I’d made, mainly the contour models, like the model of the campus, where one cuts layers of contours to put together in order to get a rise in the landscape. And I felt that this was a very good medium or technique for sculpture which had not been tried before … a theoretical landscape that was turned into a sculpture. Once I had made things in wood, I cast them in bronze.

Then I was given permission to do a large work, similar to the one for Japan. It stands in the front atrium of the Ernst and Young building in Kent Street.

But there weren’t many commissions. Sculpture wasn’t really accepted at that time: we were considered a bit weird… But sculpture now has really taken off. And I’m not patting myself on the back, but I do think we’ve done something about it, you and I. I couldn’t have done it without your enthusiasm and encouragement. And John Robertson [who worked in Buildings and Grounds]. You and John and myself, we were the ones who started the Sculpture Park.

It was such a beautiful campus, it just needed it, didn’t it? I’ve always been in love with this campus. It all happened because of a leaky tap in a flat I owned in Epping Road that I had to fix. It was a morning in May, such a beautiful morning. I went for a walk across the campus, and I had an idea. You know one must never throw an idea away. If you get a good idea, it’s got to be used.

So I knocked on the door of Buildings and Grounds and said, ‘Help, who should I see about doing a Sculpture Park?’

Jan Bohan took me by the ear and marched me to you… And within an hour of having the idea, it was all agreed.

Postscript, by Di Yerbury

I remember that. He said that he had an offer that he hoped I couldn’t refuse, and that we should get together to explore it. But first he and other sculptors wanted to congratulate me because I had such a beautiful Sculpture Park at Macquarie. ‘I have?’ I said, surprised. ‘But where are all the sculptures?’

‘Ah,’ said Errol meaningfully, ‘that’s where we come in…’

Now it’s Australia’s biggest public Sculpture Park, and this year Errol received the OAM in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List, in part for his work in curating the Sculpture Park over the past decade.

Acknowledgments, by Errol Davis

I wish to show my sincere gratitude to all those whose encouragement and forbearance have given me support in the preparation of my work for this Retrospective exhibition, especially to Peter Stanbury, Rhonda Davis and Kirri Hill, and to Effy Alexakis, Michelle Wilson and Mario Bianchino, all from Macquarie University.

A big special thank you to Di Yerbury, whose years of support have given me confidence in my work, and indeed without whom I could never have made it as far as this.

Yet there are others whose help and encouragement are much appreciated. These are Linda Klarfeld, Stella Downer and Mark Davis, who all contributed their time and energy.

Thank you to all gallery and administration staff at Macquarie University who helped to make this Retrospective exhibition a realisation.

And finally, my thanks and appreciation is extended to my family who have supported me throughout my career.

Whilst they were not meant to represent birds, some of my sculptures are birdlike. I had just been to Kakadu National Park and I was very enthusiastic about giving them names like Kakadu Flight and Jabiru and so forth.

I was making my own relief maps as sculptures… I wanted to have space and light on both sides of each contour… instead of being joined flatwise together I was able to open them out like pages of a book. I exploded my contours.

Unless otherwise noted, photography on this page is © Effy Alexakis, CFL Macquarie University and Matthew Zonca, 2002.

The text and image content on this page has been reproduced with the kind permission of Macquarie University, and is based on their 2002 publication Errol B Davis Retrospective 2002, which contains the following copyright information:

Published in 2002 by Macquarie University, Australia.

Produced to coincide with the exhibition Errol B Davis Retrospective, presented at Macquarie University Art Gallery, 21 October – 28 November 2002

Curated by: Di Yerbury

Editor: Di Yerbury

Design and Production: Crixa Convergent Media Pty Ltd

Printing: Inkolour, Steven Crump

Photography by: Effy Alexakis (unless otherwise indicated)

Co-ordinators: Rhonda Davis and Kiralynne Hill

ISBN: 0 646 41958 7

Copyright Macquarie University

All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing permitted under the copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers.