Model of Ancient Rome

It is often remarked that Rome wasn’t built in a day. In fact, it took about six months. At least, that’s how long it took Errol Davis to build his scale model of the ancient city – his largest modelmaking project. Constructed on a scale of 1:1200, it’s just over 5.8 square metres in size.

Made in 1976 as a teaching aid for the Department of Classics at the Australian National University, some of the buildings are removable to depict Rome in earlier periods. For instance, the model of the Colosseum can be removed to show the lake on which the actual Colosseum was built; and the Palatine buildings can also be removed to show the original green hill.

Model of Rome

221 x 263cm; scale 1:1200

This scale model of ancient Rome shows the centre of the city at about the end of the second century AD, although some later buildings down to the time of Constantine (early fourth century) are included. It was made by Errol B. Davis of Sydney in 1976. He used as his basis a contour map of Rome and photographs of the large model of ancient Rome in the Museo della Civiltà Romana in Rome.

The contoured base is of fibreglass and the buildings are mainly of wood and perspex. Major buildings and commemorative arches and columns, surviving or known from archaeological research, are represented in some detail. Areas which were largely residential and about which little is known are represented notionally.

The centre of the ancient city (viewed here from the south) is defined by the curve of the Tiber to the west and the early Republican Servian Wall to the east. In the foreground is the Circus Maximus, used for chariot races. Behind it, to the north, is the Palatine Hill, a fashionable residential area during the Republic, but largely given over to the palaces of the emperors in the imperial period. The Aqua Claudia aqueduct supplied it with water. Another aqueduct, the Aqua Virgo, flowing from the north, supplied the Campus Martius, the large area within the bend of the river.

The Roman Forum, the commercial and political centre of Rome, lies between the Colosseum and the Capitoline Hill. On the Capitoline is the large Temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva.

To the side of the old Roman Forum are fora built by Julius Caesar, Augustus, Vespasian, Nerva and Trajan. The last of these has in it a marble column, ca 30 m. high, carved with a spiralling relief showing Trajan’s campaigns on the Danube frontier.

Near the Tiber Island is the Theatre of Marcellus, still there today, and the Theatre of Balbus, and a little further away the Theatre of Pompey with its great arcaded forecourt where Julius Caesar was murdered. This was the first permanent theatre built in Rome.

Beyond another theatre is the Stadium of Domitian, the outline of which is preserved today by the Piazza Navona.

To the east of this is the domed and gilded bronze roof of the Pantheon, a cylindrically shaped temple made of brick-faced concrete which survives in almost its original state.

The main road north out of Rome, the Via Flaminia, is at an angle a few degrees to the west of the centre line of the model. At the edge of the model it passes Augustus’ marble Altar of Peace. Next to it is the great circular Mausoleum of Augustus. When the Altar of Peace was excavated in 1937 from under a Renaissance palace it was re-erected on the other side of the mausoleum, beside the Tiber.

Across the river, on the left-hand side of the model is the Mausoleum of Hadrian, now the Castel Sant’ Angelo, near the Vatican today.

The two large building complexes towards the right-hand side of the model are the vast Baths of Diocletian, still there opposite Rome’s main railway station, and the Baths of Trajan, built above the preserved remains of Nero’s Golden House.

The Baths of Caracalla, which still stand to an impressive height, are some distance to the southeast of the Circus Maximus, and so not on the model.

Thank you to the Australian National University for their kind permission to reproduce the text above and below; and to Bob Miller for his kind permission to use his photographs below, all of which have been sourced from the ANU Classics Museum website.

Why is Errol’s model of Rome so significant to the Classics Museum collection?

Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Minchin, the Museum’s Curator, observes that the model has a strong physical presence.

“It stands in the centre of the museum space and is thus a focus for all eyes,” she says.

But its significance comes also from the fact that humans love three-dimensional representations of space and the capacity of landmarks for prompting stories.

“On this model of Rome we can locate the site of Julius Caesar’s assassination by his fellow senators; we can locate the settings that the historian Livy describes when he sets out the early history of Rome; or, on the other hand, we can pinpoint the settings which the poet Ovid recommends for social encounters with the opposite sex. This model enables us to bring the world of ancient Rome to life.”

Professor Minchin fondly recalls a university Open Day when a visitor to the Classics Museum was so inspired by seeing the model that she decided to study Classics! If you, too, are in need of some inspiration, you can see Errol’s iconic model for yourself – as well as the Classics Museum’s impressive collection of ancient artefacts – in the A.D. Hope Building (entrance off Ellery Crescent) on the ANU campus. Please check the Classics Museum website for opening hours.

Closeup of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, also known as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus.

Regarded as the most important temple in Ancient Rome, located on the Capitoline Hill, 509 BC – 83 BC.

Thank you to the ANU for their kind permission to reproduce this image, which was sourced from the ANU website.

Ancient Rome Comes to ANU

The following is the text of an article (an image of which appears below) that appeared in the ANU Reporter, 30th April 1976. Text and image reproduced with the kind permission of the Australian National University.

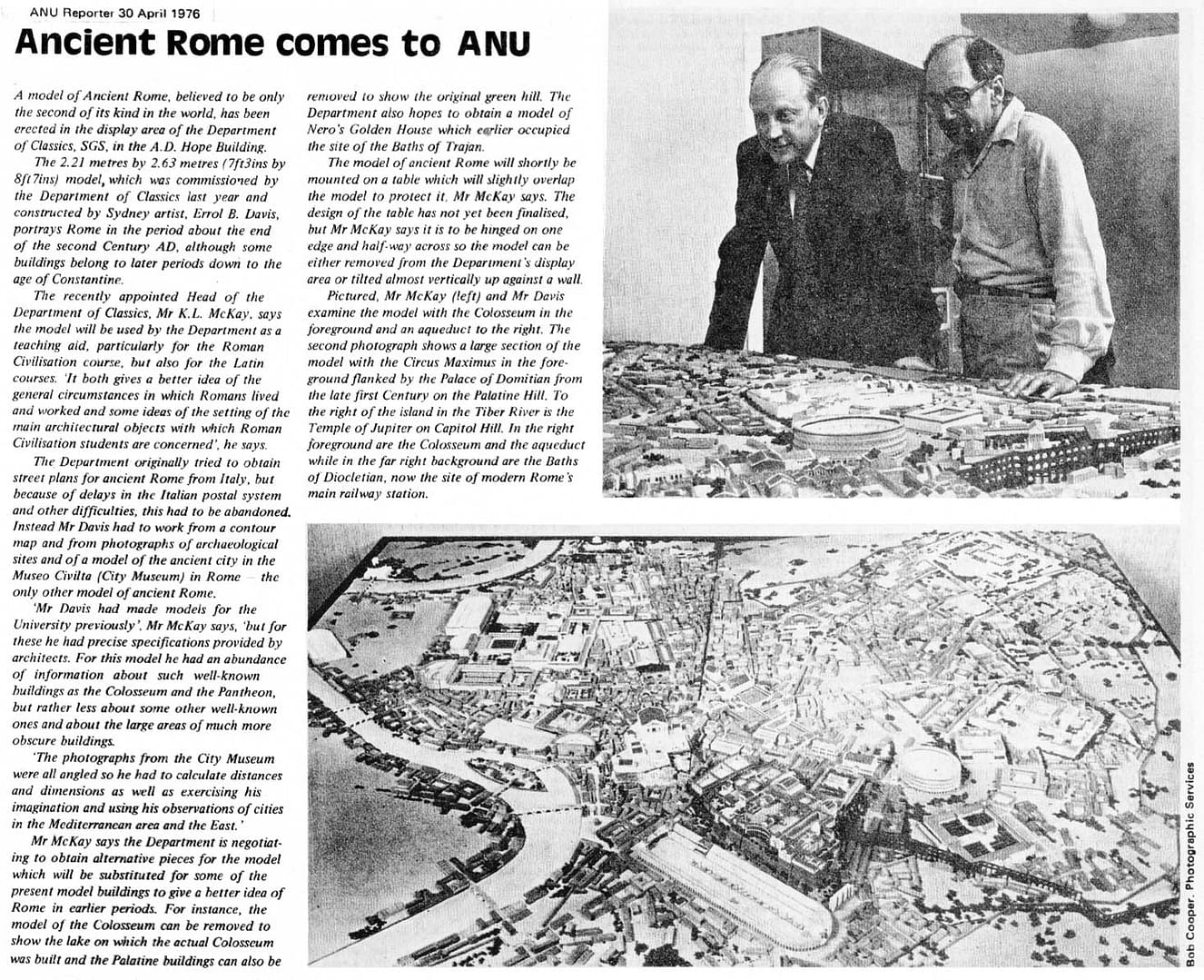

A model of Ancient Rome, believed to be only the second of its kind in the world, has been erected in the display area of the Department of Classics, SGS, in the A.D. Hope Building.

The 2.21 metres by 2.63 metres (7ft3ins by 8ft7ins) model, which was commissioned by the Department of Classics last year and constructed by Sydney artist, Errol B. Davis, portrays Rome in the period about the end of the second century AD, although some buildings belong to later periods down to the age of Constantine.

The recently appointed Head of the Department of Classics, Mr K.L. McKay, says the model will be used by the Department as a teaching aid, particularly for the Roman Civilization course, but also for the Latin courses. ‘It both gives a better idea of the general circumstances in which Romans lived and worked and some ideas of the setting of the main architectural objects with which Roman civilization students are concerned’, he says.

The Department originally tried to obtain street plans for ancient Rome from Italy, but because of delays in the Italian postal system and other difficulties, this had to be abandoned. Instead, Mr Davis had to work from a contour map and from photographs of archaeological sites and of a model of the ancient city in the Museo Civilta (City Museum) in Rome – the only other model of Ancient Rome.

‘Mr Davis had made models for the University previously’, Mr McKay says, ‘but for these he had precise specifications provided by architects. For this model he had an abundance of information about such well-known buildings as the Colosseum and the Pantheon, but rather less about some other well-known ones and about the large areas of much more obscure buildings.

‘The photographs from the City Museum were all angled so he had to calculate distances and dimensions as well as exercising his imagination and using his observations of cities in the Mediterranean area, and the East.’

Mr McKay says the department is negotiating to obtain alternative pieces for the model which will be substituted for some of the present model buildings to give a better idea of Rome in earlier periods. For instance, the model of the Colosseum can be removed to show the lake on which the actual Colosseum was built and the Palatine buildings can also be removed to show the original green hill. The Department also hopes to obtain a model of Nero’s Golden House which earlier occupied the site of the Baths of Trajan.

The model of Ancient Rome will shortly be mounted on a table which will slightly overlap the model to protect it, Mr McKay says. The design of the table has not yet been finalised, but Mr McKay says it is to be hinged on one edge and half-way across so the model can be either removed from the Department’s display area or tilted almost vertically up against a wall.

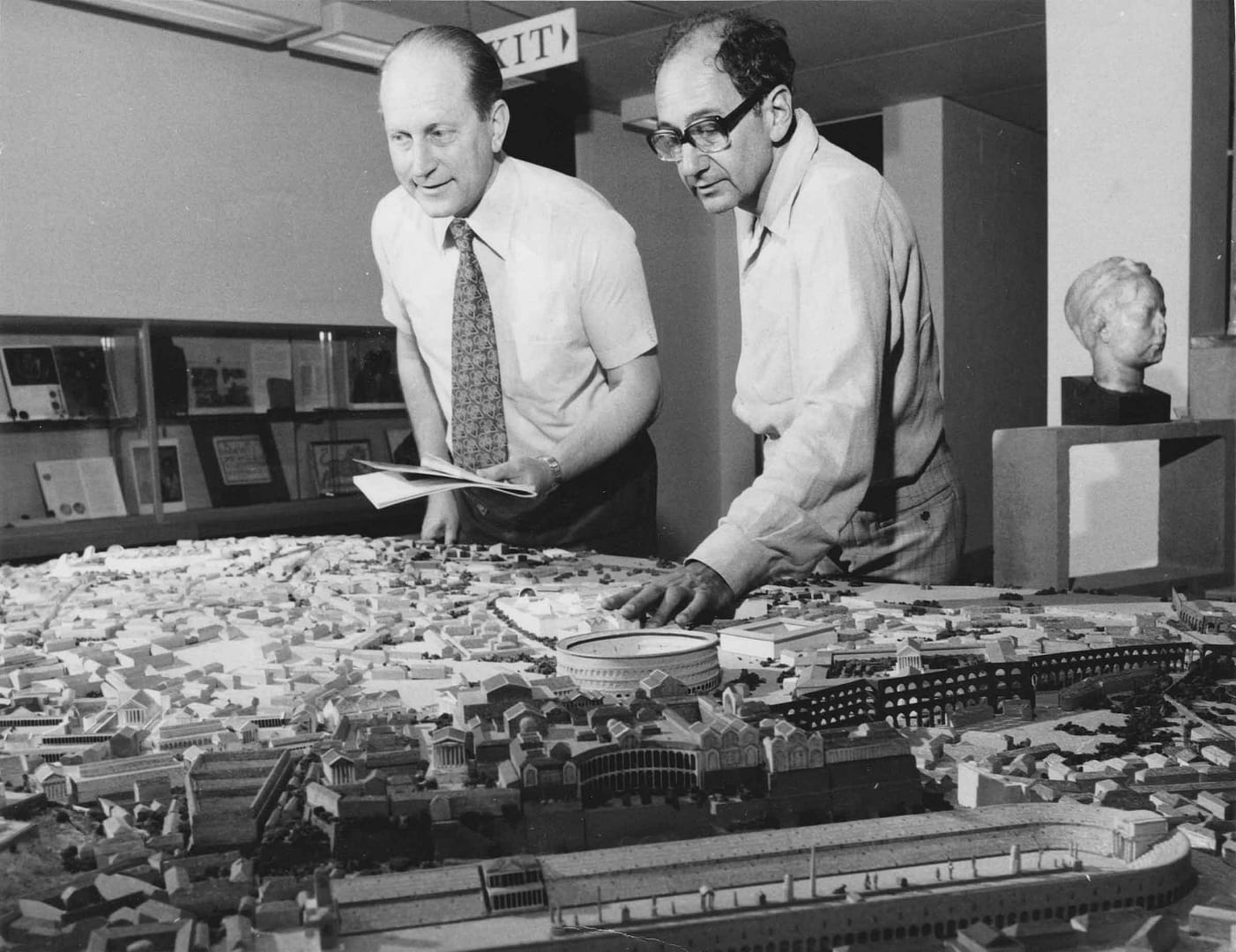

Pictured, Mr McKay (left) and Mr Davis examine the model with the Colosseum in the foreground and an aqueduct to the right. The second photograph shows a large section of the model with the Circus Maximus in the foreground flanked by the Palace of Domitian from the late first Century on the Palatine Hill. To the right of the island in the Tiber River is the Temple of Jupiter on Capitol Hill. In the right foreground are the Colosseum and the aqueduct while in far right background are the Baths of Diocletian, now the site of modern Rome’s main railway station.

The interior of the ANU Classics Museum, with the model of Ancient Rome. Photograph © Nick-D.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 1.0 Generic license.